Guns and Butter of the South

The Confederate Agrarian Economy On Eve of War: A Geospatial Perspective

It’s one of the most memorable scenes in American cinema. Georgia, April 1861: a throng of foppish young gentlemen toast to a quick victory over the Federal government. “One Southerner can lick twenty Yankees,” they proclaim, “Gentlemen can always fight better than rabble!” Amidst the excitement, Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler is asked for his opinion on the state of play between North and South. Placid, dark-haired, with a cynical smirk, he speaks like Cassandra, prophesying the ruin of the slave states’ cause at the hands of Northern industry, scoffing at his companions’ naivete. The room erupts in scandalized protest before Rhett makes a sardonic concession and takes his leave. Within a few years, most of the young gentlemen in the room would be dead, their bodies never recovered, their families reduced to scrounging for roots in the dirt.

This scene from Gone With the Wind embodies much of our popular conception of the secession body-politic: we think of the Confederacy as a romantic and foolhardy people who read too much Walter Scott, brought an agricultural economy to an industrialized economy’s fight, then starved and withered under insurmountable odds. We remember Pickett’s Charge and the Richmond Bread Riots and marvel at these simple agrarians, whom we believe carried on the struggle for four years only by their tenacious spirit, doomed without meaningful infrastructural development or productive capacity. If we were to be reunited with the leaders of the Confederacy today, we might channel both Rhett Butler and Band of Brothers’ Private Webster and cry out, “What were you thinking? All you had was cotton, slaves, and arrogance!”

The historical record, however, reveals a much different image of southern agrarianism. Before the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the territories that became the Confederate States of America had built up a robust and productive economic system, which, while not modernized to the extent of their northern neighbors, utilized industrial-era botanical science, diversified regional agriculture, and 19th-century transportation to their greatest advantage. While the character of this economic system was unmistakably based in slave agriculture, it was not run by wide-eyed Ivanhoe cavaliers lost in time: it was fully integrated with an emerging capitalism that lined the pockets of its operators in peacetime and could have well provided for its soldiers, state, and citizens in wartime.

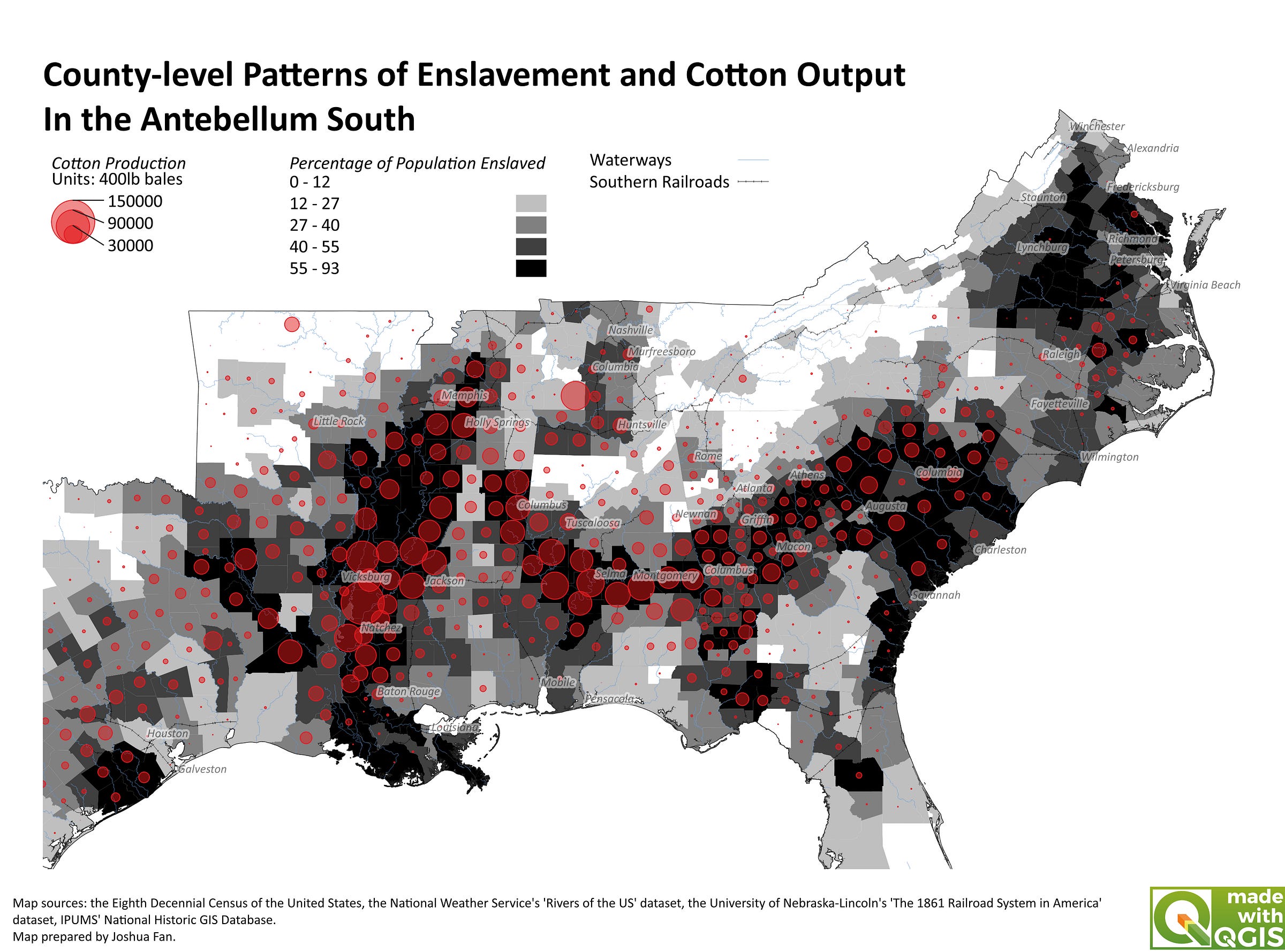

That the economy of the antebellum South was reliant on enslaved production of cash crops—cotton the most significant among these—is uncontestable. The above map demonstrates the strong geographic correlation between slavery and cotton production. The Mississippi watershed, most notably the Delta and embayment regions north of the Gulf Coast, and the Black Belt running northeast in a curve across Alabama, Georgia, and into the Carolinas, were simultaneously the most cotton-intensive agricultural regions and the areas that most heavily employed slave labor.

While the dominance of cotton production had been established since the invention of Whitney’s gin,1 1860 was a particularly prosperous moment for the Southern cotton industry because of a particularly strong market throughout the 1850s. The late Antebellum was a boom period for cotton prices, and as such the annual Southern cotton crop doubled to over five million bales from 1850 to 1860, and the cotton trade became an increasingly significant destination for Southern capital—while per capita investment in Southern manufacturing increased by 39% from 1850 to 1860, the average price of slaves appreciated 70% and agricultural land value rose 72%2.

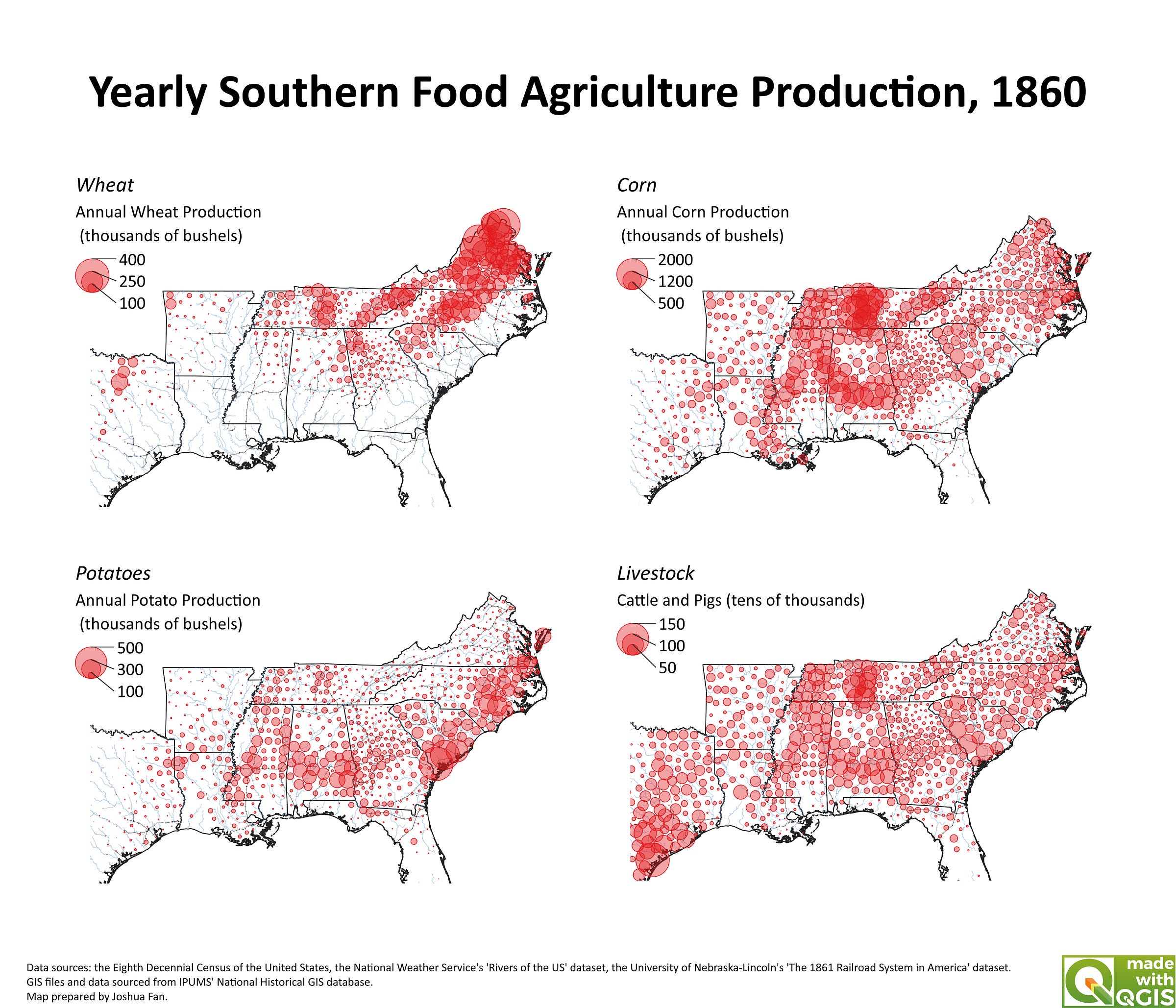

Did the South’s prewar cotton boom come at the expense of subsistence crops like wheat, corn, or potatoes? Per capita harvests of staple foods did decline over the 1850s, moving the region toward the paradox of becoming a food-deficient agricultural economy.3 But the per capita data obscures a more complex picture: in absolute terms, subsistence crop production remained resilient, and often even grew, alongside the expanding cotton trade.

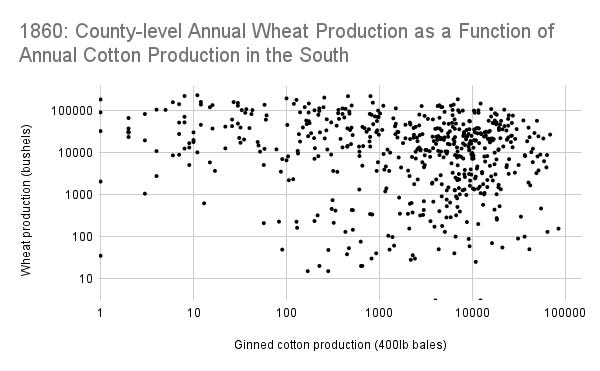

This plot of county-level data shows that while Southern cotton production was negatively correlated with that of wheat, this negative relationship may not have been so strong.4 The data here is not suggestive of a causal relationship where an increase in cotton production led to a corresponding decrease in the wheat harvest.

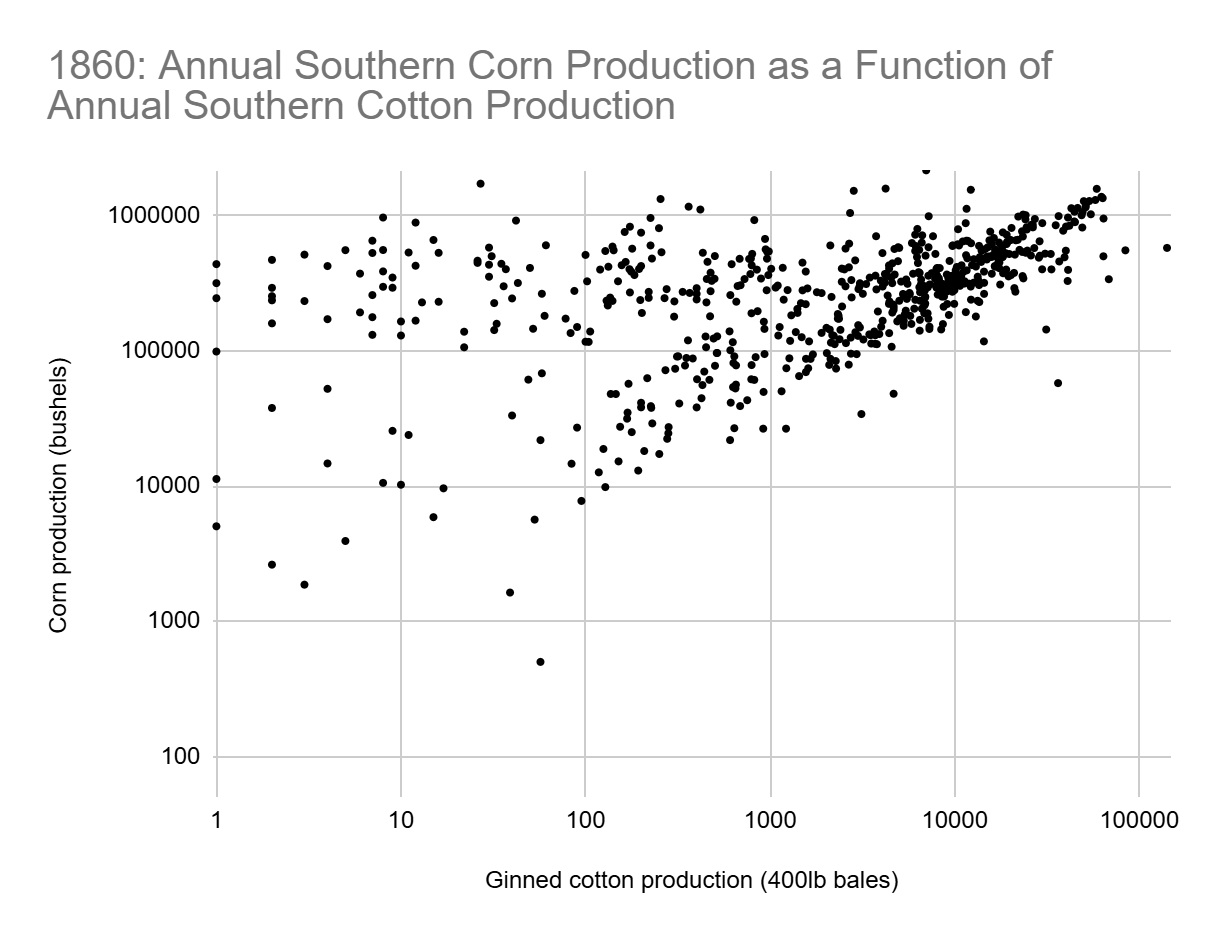

Notably, corn and cotton have the opposite relationship, with a positive correlation between their production, and a much strong r-squared. Other food products including hogs, sweet potatoes, peas, and beans follow similar trends. Data from the 1860 census suggest absolute increases in cotton production were correlated with absolute increases in major food products.

The resilience of absolute subsistence crop yields in the face of the expanding cotton trade can be partially explained as a result of the Southern agricultural reform movement which began in the 1840s. Following the shock of the Panic of 1837, the planter class began advocating crop diversification and rotation as bulwarks against environmental degradation, with one South Carolinian planter declaring "It should be an inviolable rule in the economy of every plantation to produce an abundant supply of every species of grain, and of every species of livestock, required for its own consumption."5 This was an unabashedly modernist agrarian movement, inspired the scientific and managerial advances of the Industrial Revolution and rebelling against traditional agricultural practices.6 For some Southerners, reform took on a political, even ethical, weight, with some considering subsistence agriculture to be a moral duty in defense of republican individualism.7

Another major characteristic of Southern food agriculture was its regional diversity. The above map demonstrates some illustrative examples: wheat was most extensively cultivated in the Upper South, especially in Virginia; potatoes were mostly grown in the Alabama Black Belt and the coastal Carolinas; and corn was produced in most fertile regions east of the Mississippi. Rice was almost exclusively grown in the Carolinas by 1860, and while hogs were raised in most regions of the South, Texas was the uncontested champion of the beef industry. Overall, highly productive and adaptable goods like corn or hogs saw more widespread production, but there was still strong regional variation in subsistence product output. The statistical relationship between cash crop output and subsistence was likely often a result of this variation, and not of purely economic factors.

A constant element of both cash crop production and subsistence agriculture was the exploitation of slave labor. While the memory of slavery is today heavily associated with the horrific cruelty of the cotton plantation, slavery’s entrenchment in Southern society and economy ran beyond cash crop agriculture, and food production was also inextricably linked with human bondage. In 1860, counties with higher percentages of enslaved populations tended to output more cotton, but also tended to produce more beef, hogs, potatoes, peas, beans, and corn. A major implication of the connection between food agriculture and slavery was that the Confederate States would be able to fill their regimental rosters with white smallholders without too much degradation of their farming capacity, as the slaves on the home front would continue cultivating the fields.

The rebel states thus went into the war with a highly productive and diversified agricultural base and could freely draw from the yeoman class for their all-white army, confident that the slaves they held in bondage would continue reaping their harvests for the duration of the conflict. The last piece of the puzzle is distribution. What good is all the food in the world if it cannot be transported easily and quickly?

The common assertion that the Confederate States’ railway infrastructure was woefully underdeveloped and primitive is mostly based in comparison to the North and fails to reflect the reality of the Southern rail network on the eve of war. Statistical comparisons make clear the North’s railways were indeed more developed than that of the South: in 1861 the secession states possessed only a third of national railway mileage, one third of the freight cars, and one fifth of the locomotives.8 However, the Southern railway system and rail industry were far from impotent: in the 1850s they more than quadrupled their railroad mileage (outpacing the rate of growth in the free states),9 matched the North’s per capita rate of capital investment in rail production, and by the end of the decade possessed the world’s third largest rail system, only behind the North and Great Britain.10 While underdeveloped compared to that of their northern neighbors, the slave states’ railroad system was plenty capable and was entirely sufficient for supporting their war effort.

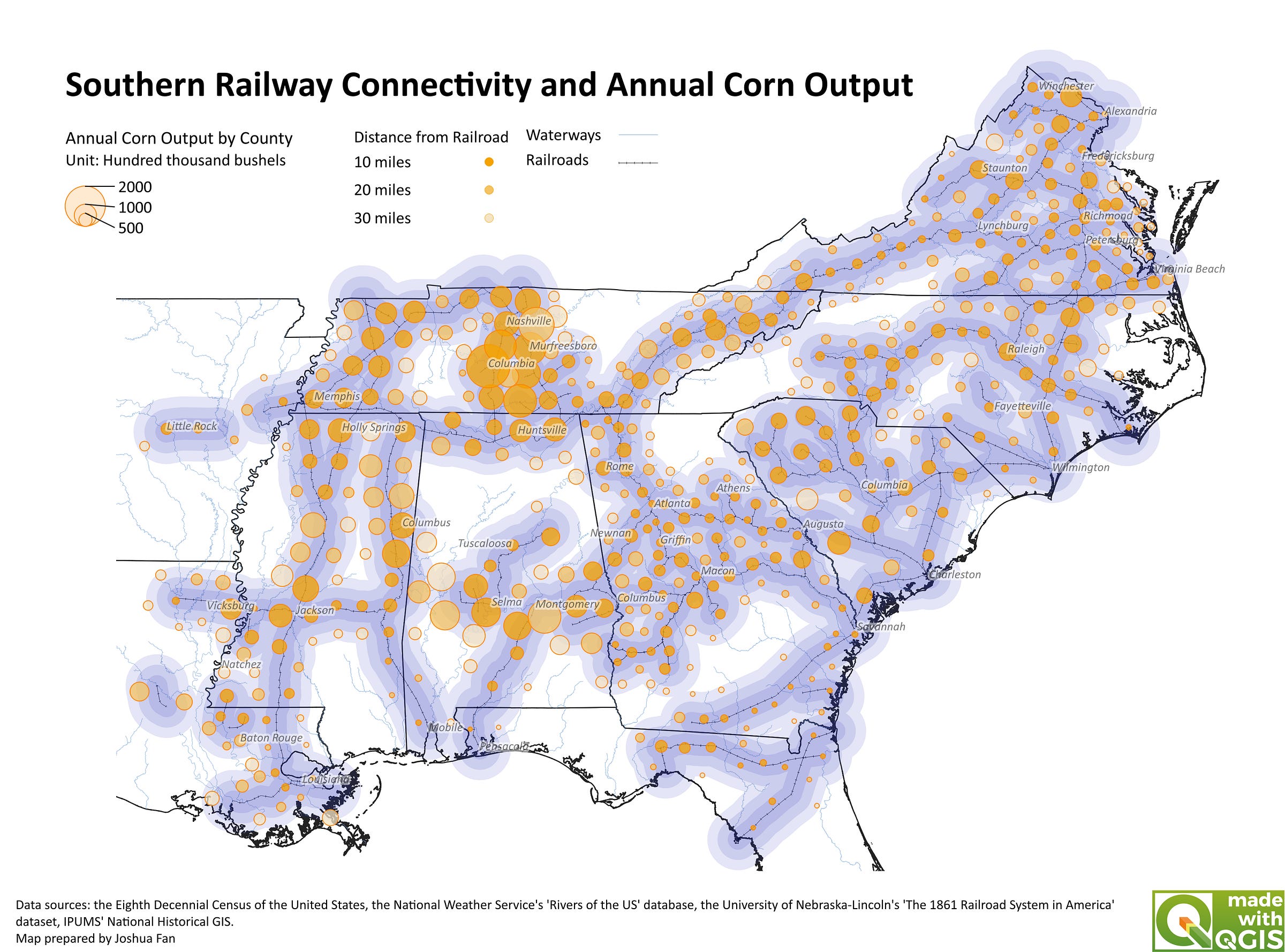

The Southern rail network was tightly intertwined with agricultural industry and built to support rapid access and shipment of farmed goods. The map above depicts the level of integration between Southern rail transit and the subsistence economy using the example of corn yields. In general, railroads were laid out along highly productive regions, facilitating movement of agricultural products across the slave states.

My analysis of Southern railways and county-level data on agricultural yields indicates that around 52.3% of all wheat, 43.7% of all corn, 42.2% of all cotton, and 40.9% of all hog production lay within 10 miles of the railways. More than 80% of major Southern crop production and 76.5% of hog production lay within 30 miles of the rail network. This demonstrates an advanced level of internal economic integration which would have afforded the Confederate States the means for large-scale logistical efforts. Flour, cornmeal, legumes, potatoes, and pigs could be easily moved by railcar from one state to another, from farms in Alabama to camps along the Rappahannock.

The reality of the South’s agricultural economy puts the lie to David O. Selznick’s Technicolor hallucination of the simple agrarian living in a “Civilization gone with the wind.” This was a modernized, 19th-century system of colossal productivity, scientific management, regional diversity, exploitation of slavery, and integration with rail industry.

Understanding the South’s true economic foundation forces us to restore agency to the Confederacy and to reconsider why they lost. If we buy into the narrative of the South’s inherent economic disadvantage, we might believe that defeat was inevitable. Predestination would absolve Confederate leadership of their logistical mismanagement, strategic impotency, political incompetence, and human fallibility. They were not doomed from the start—they doomed themselves: by mismanaging their railway system; by surrendering crucial territory in the west through military neglect; and by engaging in internal feuds, leaving thousands of their soldiers dead on the battlefield and swathes of their country devastated. The white South’s decision to secede from the Union was itself a disaster, and throughout the war they only went from catastrophe to catastrophe.

The myth of the agrarian underdog recasts farce as tragedy and obscures the truth: for the Confederate States of America, the fault was not in their stars, but in themselves.

Bibliography and Map Sources

Collins, Stephen. 2001. “System, Organization, and Agricultural Reform in the Antebellum South, 1840-1860.” Agricultural History 75 (1): 1-27.

Ford, Lacy. 1985. “Self-Sufficiency, Cotton, and Economic Development in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860.” Journal of Economic History 45 (2): 261-267.

Gabel, Christopher. 2002. Rails to Oblivion: the Decline of Confederate Railroads in the Civil War. N.p.: Army University Press.

Manson, Steven, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, Katherine Knowles, Tracy Kugler, Finn Roberts, and Steven Ruggles. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 19.0, 1860 Census. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V19.0.

McPherson, James M. 2003. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. N.p.: Oxford University Press, USA.

National Weather Service. NWS GIS Portal, “Rivers of the U.S.” NOAA, 2007.

Thomas, William G, and University Of Nebraska. Dataset of the railroad system in America. [Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, © 2006 to, 2017] Software, E-Resource. https://www.loc.gov/item/2020446879/.

Lacy Ford, “Self-Sufficiency, Cotton, and Economic Development in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860,” Journal of Economic History 45, no. 2 (1985): 261.

James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press, 2003), 99.

McPherson, 100.

Interestingly, the shape of the scatter plot vaguely resembles the classic concave-down Production Possibilities Frontier from every Econ 101 class.

Ford, 264.

Stephen Collins, “System, Organization, and Agricultural Reform in the Antebellum South, 1840-1860,” Agricultural History 75, no. 1 (2001): 14.

Ford, 264.

Christopher Gabel, Rails to Oblivion: The Decline of Confederate Railroads in the Civil War (Army University Press, 2002), 1.

McPherson, 94.

Gabel, 1-2.