Zohran Mamdani’s big primary win last week has brought a major campaign promise of his into the national spotlight: public grocery stores.

Recent discourse around city-owned supermarkets have generated a lot of buzz but much remains unknown. Beyond the fact that this is a theoretically sound policy (food insecurity is a negative externality, and city-owned grocery stores can correct for the market failure1), we can’t make conclusive statements. There is not much precedent in terms of implementation (aside from the decades-old military-operated Army and Air Force Exchange Service,2 experiments with public retailers in the US have been pretty limited in scale3). Mamdani’s proposed pilot program will therefore serve as an important litmus test for the American implementation of public grocery stores. For me, one question remains paramount: where should the city place its new municipally operated grocery stores?

Intuitively, it should be pretty simple: just put the supermarkets in the food deserts! Everybody knows that in America we have these places called “food deserts,” or “neighborhoods and communities that have limited access to affordable and nutritious foods,” usually located in low-income regions.4 Research into food deserts often focuses on low-income areas, and policies aimed at alleviating food insecurity typically target these areas as well.

However, a look at the geography of food insecurity in New York City shows that the challenges of food insecurity may have evolved past established notions of the “food desert.”

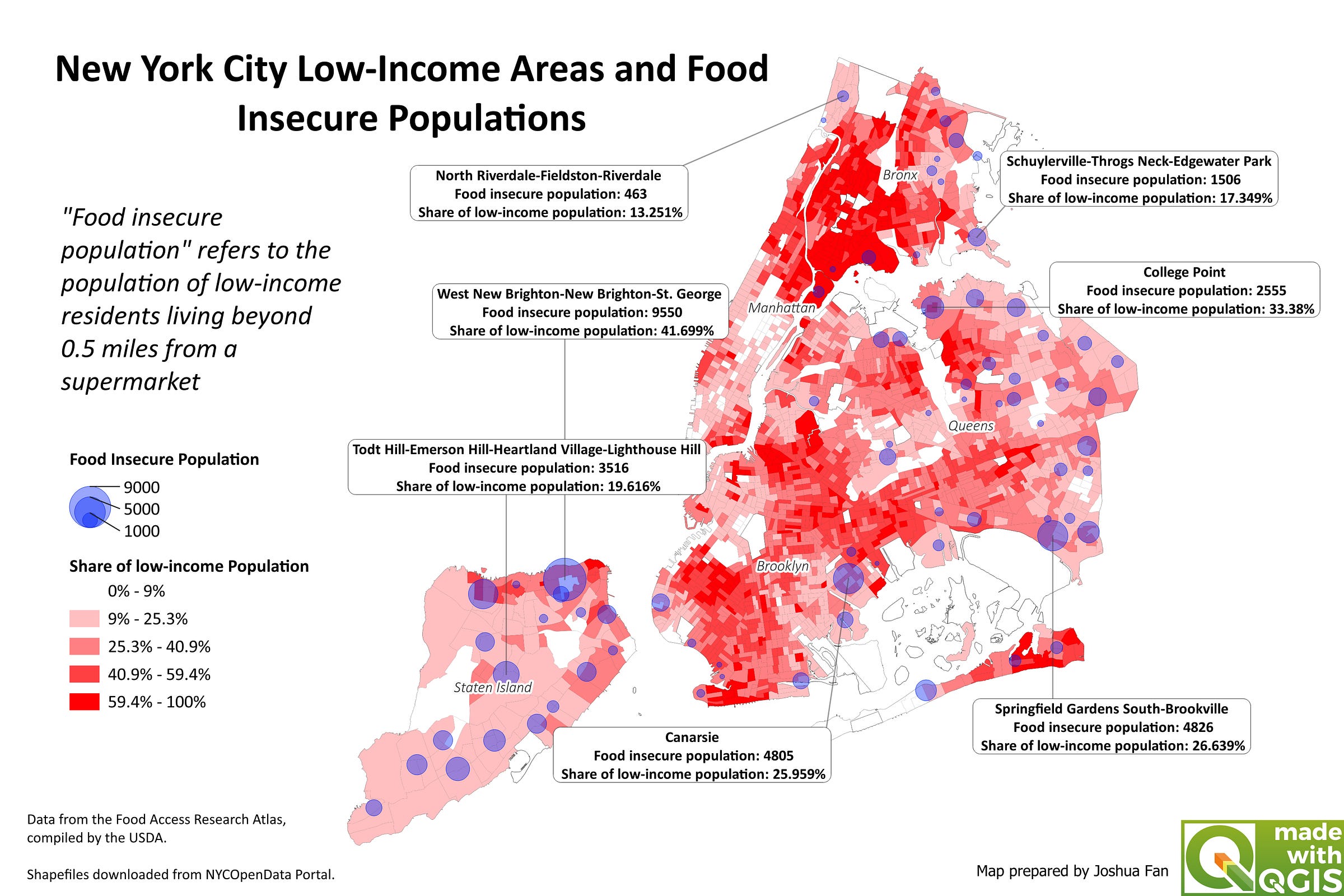

Using data from the USDA’s 2019 edition of the Food Access Research Atlas, I compiled this map plotting the concentrations of food insecure populations in New York City over a graduated display of low-income rates across the city.

Notably, the food insecure population in the poorest neighborhoods is nearly nonexistent. Rather, food insecure populations seem to be concentrated around the low-income hotspots, in neighborhoods with moderate or low rates of poverty.

This indicates that the concept of the “food desert” as a fixed geographic area correlated with low-income may not reflect the reality of urban food insecurity. Instead of conceptualizing the “food desert” as a specific location or community, we might be better served thinking of it as a condition applying unevenly to residents of the same community. The majority of those currently impacted by lack of access to fresh food do not live clustered together. Instead, they live in neighborhoods intermingled with wealthier residents.

This complicates the question of public supermarket placement by disrupting the idea that there are easily definable areas more in need of these stores. Compounding the issue is the impact of pre-existing policy.

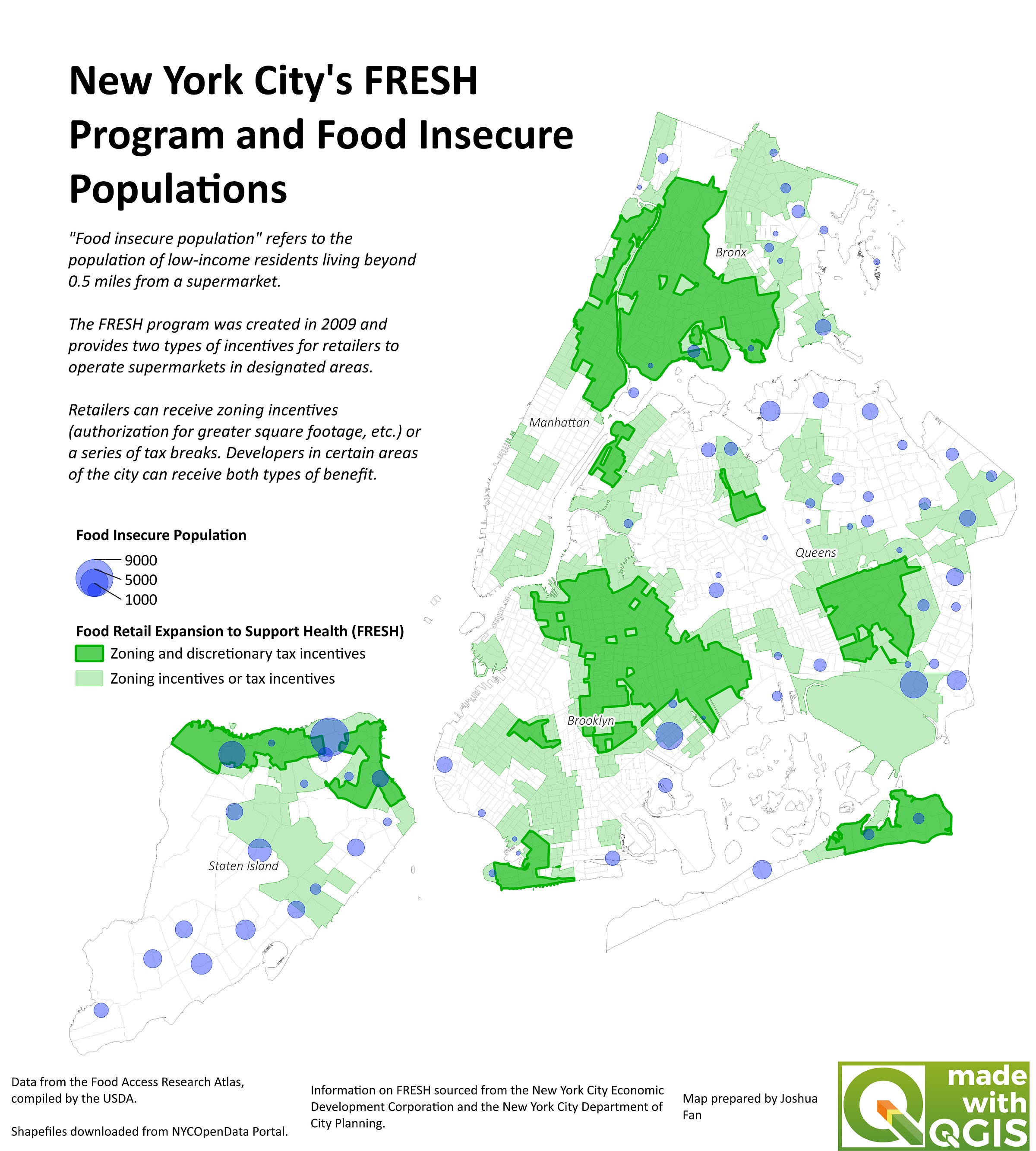

Public grocery stores would only be another tool of many that the city government could implement for the purpose of food insecurity alleviation. New York already has a market-and-zoning-based system promoting the development of supermarkets in designated areas, called the Food Retail Expansion to Support Health program (FRESH).5

This map of food insecure populations and FRESH zones reveals an explanation for the perplexing non-existence of the textbook food desert in New York City: it’s survivorship bias.

The combination of zoning and tax incentives for retail developers seems to have been effective at alleviating food insecurity in the areas of FRESH’s enforcement. The food insecure population in FRESH zones with both zoning and tax benefits for developers—the more impoverished regions of New York—is virtually nonexistent. This map demonstrates a resoundingly successful implementation of policy.

Public grocery stores, market intervention, and city planning intervention could be used in conjunction by the city government in a belt-and-suspenders approach. However, applying too many policies aimed at the same outcome in the same areas could lead to diminishing returns. If food insecurity has been meaningfully eliminated in the poorest neighborhoods of New York through FRESH, why build the city-owned grocery stores there when there are so many food-insecure people living in other communities?

To be clear, I am not entirely advocating for public supermarkets to be built in neighborhoods with moderate or low rates of poverty. Those communities may have certain socioeconomic dynamics that present challenges for the public grocery store. Without implementation nobody can really say. My point comes down to this: the problem of food insecurity in New York currently exists in a form defying expectations, and government decisions have to be targeted for this moment’s unique circumstances. Policy and markets have left people in the gray zone of food insecurity behind, and adopting the municipal grocery store provides an opportunity to focus on their plight.

Covert, Bryce. 2025. “Can government-owned grocery stores help solve America's food-desert problem?” Food and Environment Reporting Network, March 24, 2025. https://thefern.org/2025/03/are-government-owned-grocery-stores-the-answer-to-americas-food-desert-problem/

Schweizer, Errol. 2025. “New Yorkers Voted For Public Grocery Stores. How Would That Work?” Forbes, June 27, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/errolschweizer/2025/06/27/why-new-yorkers-want-public-grocery-stores/.

Pattison-Gordon, Jule. 2025. “Should Cities Open Their Own Grocery Stores?” Governing Magazine, January 10, 2025. https://www.governing.com/urban/should-cities-open-their-own-grocery-stores.

“Introduction.” 2009. In The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts: Workshop Summary. N.p.: National Academies Press.

“Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH).” n.d. New York City Department of City Planning. https://www.nyc.gov/content/planning/pages/our-work/plans/citywide/food-retail-expansion-support-health-fresh.